Re: development – Inside The Green Backyard

A collaborative networked exhibition

28 March – 1 May 2017

Jessie Brennan 'Toothbrush', cyanotype, Inside The Green Backyard (Opportunity Area), 2015-16

After five years hard work by its volunteers and incredible public support, The Green Backyard, a community growing project in Peterborough run entirely by volunteers, is no longer threatened with redevelopment: the owners of the land, Peterborough City Council, have offered a rolling 12-year lease. Re: development – Inside The Green Backyard is a collaborative networked exhibition, which celebrates the success of The Green Backyard's campaign to safeguard the land. The exhibition features cyanotypes (camera-less photographs of objects from the site) and voice recordings (oral testimonies by the volunteers) from Jessie Brennan's work Inside The Green Backyard (Opportunity Area), 2015–16, an outcome of Jessie's year-long residency with The Green Backyard and arts organisation Metal. More about Jessie's residency project can be found here in an article she wrote for the Guardian.

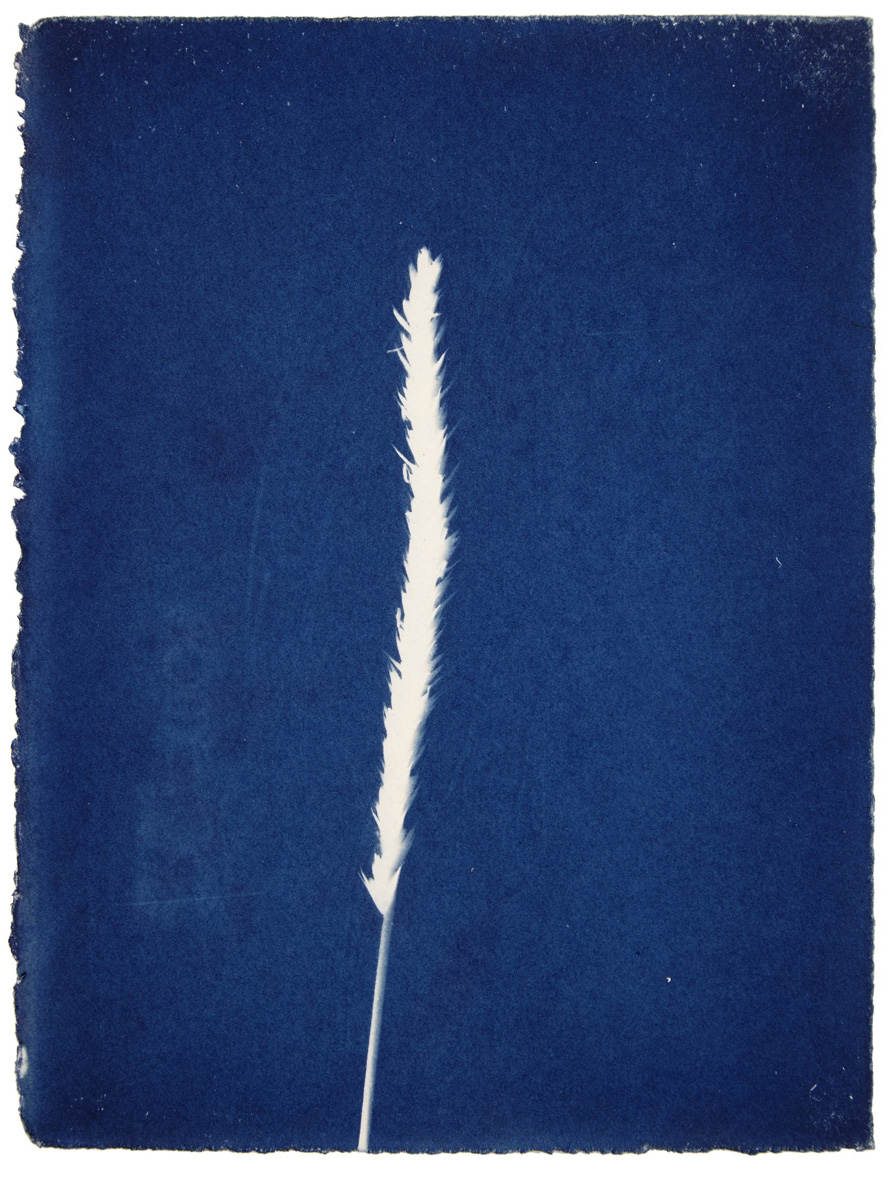

Jessie Brennan, 'Timothy-grass', cyanotype, Inside The Green Backyard (Opportunity Area), 2015-16.

Anna Hunt, volunteer (Plantain)

Links to other exhibits (in alphabetical order):

Re: development: Voices, Cyanotypes & Writings from The Green Backyard

Introduction

Jessie Brennan

This piece was written for Re:development, a book that brings together voices, cyanotypes and writings from The Green Backyard following my year-long residency there. Published before the land was finally safeguarded, it questions the capitalist logic of the site’s proposed development by the landowner, Peterborough City Council. The book shares the voices of The Green Backyard – of those defending their right to the city.

Jessie Brennan, If This Were to Be Lost (2016), painted birch plywood on scaffold, 1.9 x 19 m, situated at The Green Backyard, Peterborough. Photograph by Jessie Brennan

Among the borage plants there lies a toothbrush, its simple white length surrounded by vivid blue. It’s an object donated by a visitor to The Green Backyard (which is acting as a collection point) for refugees in Calais, and it is one of many hundreds of objects here that seem to invoke the voice of The Green Backyard: offering a conduit through which people close to the project can articulate its value. The objects that call forth the voice reveal, in turn, that those voices also tacitly object: through positive tactics of planting and communing, individuals speak of the necessity of The Green Backyard as public, open, urban green space, and why its proposed development must be resisted.

I first set foot inside The Green Backyard, a ‘community growing project’ in Peterborough, in May 2014, at a time when the threat of a proposed development by its owner, Peterborough City Council, was at its most heightened. What brought me to this site were questions of land ownership and value (framed by the long history of community land rights struggles) and the ‘right to the city’: whom the land belonged to.

Because, of course, feelings of belonging to a place in no way necessarily mean it belongs to you, as users – visitors, volunteers and trustees – of The Green Backyard are all too well aware. Despite the current social value that this urban green space clearly provides, debates around the proposed development of The Green Backyard (and many other volunteer-run green spaces) have been dominated by arguments for the financial value of the land – referring to the short-term cash injection that its sale would generate – rather than the long-term social benefit of the site… [continues here]

Digging for Our Lives: The Fight to Keep The Green Backyard

Sophie Antonelli, co-founder of The Green Backyard

This piece was written for Re:development, a book brought together by artist Jessie Brennan following her year-long residency at The Green Backyard. Published before the land was finally safeguarded, it traces the journey of transforming a former derelict allotment site into the thriving community growing project that is now The Green Backyard.

Jessie Brennan, If This Were to Be Lost (2016), painted birch plywood on scaffold, 1.9 x 19 m, situated at The Green Backyard, Peterborough. Photograph by Jessie Brennan

In early 2009 we first opened the gates to a site in Peterborough that had been closed and unused for 17 years. A 2.3-acre site in the city centre, next to two main roads and the East Coast main line to London should not be hard to miss, but after almost two decades of disuse many people had simply forgotten it existed. I’d like to say that we knew what we were doing at that time, but as is often the case in voluntary groups, the creation of what would become The Green Backyard was motivated by the seizing of an opportunity, in this case offered land, together with a tacit sense of need: to preserve years of learning created by my father on his allotments; to create a space for people to learn and change; and to challenge the momentum of the city, which in my life-time had seemed stagnant and apathetic.

At the time I could not have articulated these motivations, and I am now very aware that my own impetus is likely to have differed from others’ around me. I find this to be the case with many community spaces: everyone comes to them with their own very personal set of hopes and needs which are often complimentary, and occasionally divisive.

The lessons that grew out of those undefined early experiences of creating a shared space made visible the participatory qualities inherent to the project and fired up the desire for imperfect spaces – rather than meticulously planned ones, with defined budgets and personnel. The threat then imposed by the land owners, our City Council, in response to the slashing of local authority budgets following the 2008 financial crisis, actually served to crystallise this value and catalyse a movement of enthusiasm for radical change in a city long-complacent and passive.

The battle to stop the land being sold off for development, I think, surprised everyone. First came the obvious shock when council officers arrived just a few days before Christmas in 2011 and told us of their intention to sell the land… [continues here]